Hybrid attendance patterns and the rise of coffee badging

Hybrid attendance patterns are increasingly uneven, with short office visits used to meet expectations and manage visibility. Behaviors like coffee badging can signal gaps in trust, workplace norms, and office design. The pattern matters because it can skew utilization data, complicate planning decisions, and influence employee experience without implying wrongdoing.

Coffee badging has become a recognizable feature of hybrid work: people show up briefly, connect, and then leave. In many organizations it appears alongside return-to-office expectations, new attendance targets, and shifting ideas about what “being present” is meant to accomplish.

For workplace, HR, Facilities, and Real Estate leaders, the behavior is worth attention because it affects more than headcount. It changes how occupancy looks hour by hour, how employees experience the office, and how reliable workplace data is for planning decisions.

Coffee badging is often a signal of misaligned incentives: the organization is asking for visible presence, while employees are optimizing for productive time, flexibility, and energy.

Why coffee badging is becoming more visible

Hybrid work did not create short office visits, but it made them easier to observe and easier to rationalize. Several forces have converged to make the coffee badging behavior more common and more noticeable.

Attendance mandates

Many organizations introduced on-site expectations as a simple lever to increase in-person interaction. The challenge is that attendance mandates often specify days rather than outcomes. When the measure is “show up,” the most efficient way to comply can become “show up briefly.”

In practice, mandates can unintentionally encourage minimum-viable presence. Employees who do not see a clear purpose for staying longer may treat compliance as a checkbox rather than a work pattern.

Visibility pressure

In hybrid settings, visibility becomes uneven. Some people are on-site frequently, while others are remote most days. In that environment, being seen can feel like a form of risk management, especially when performance conversations are perceived to be influenced by proximity.

Coffee badging can emerge as a compromise: enough face time to reduce perceived career risk, without sacrificing the benefits of working elsewhere for focused tasks.

Hybrid work norms

Hybrid work creates legitimate reasons for short on-site windows. People may optimize for collaboration in the morning, focused work in the afternoon, or commuting outside peak hours. A brief visit can be a rational response to distributed teams, fragmented calendars, and limited overlap.

Over time, these choices become normalized, and employees start copying patterns they see around them. In that way, coffee badging behavior can spread without any explicit policy change.

Office design mismatches

Many offices were designed for a full-day rhythm: desk-based work, steady occupancy, and predictable peaks. Hybrid work changes the purpose of the office toward connection, coordination, and decision-making, but the environment does not always adapt at the same speed.

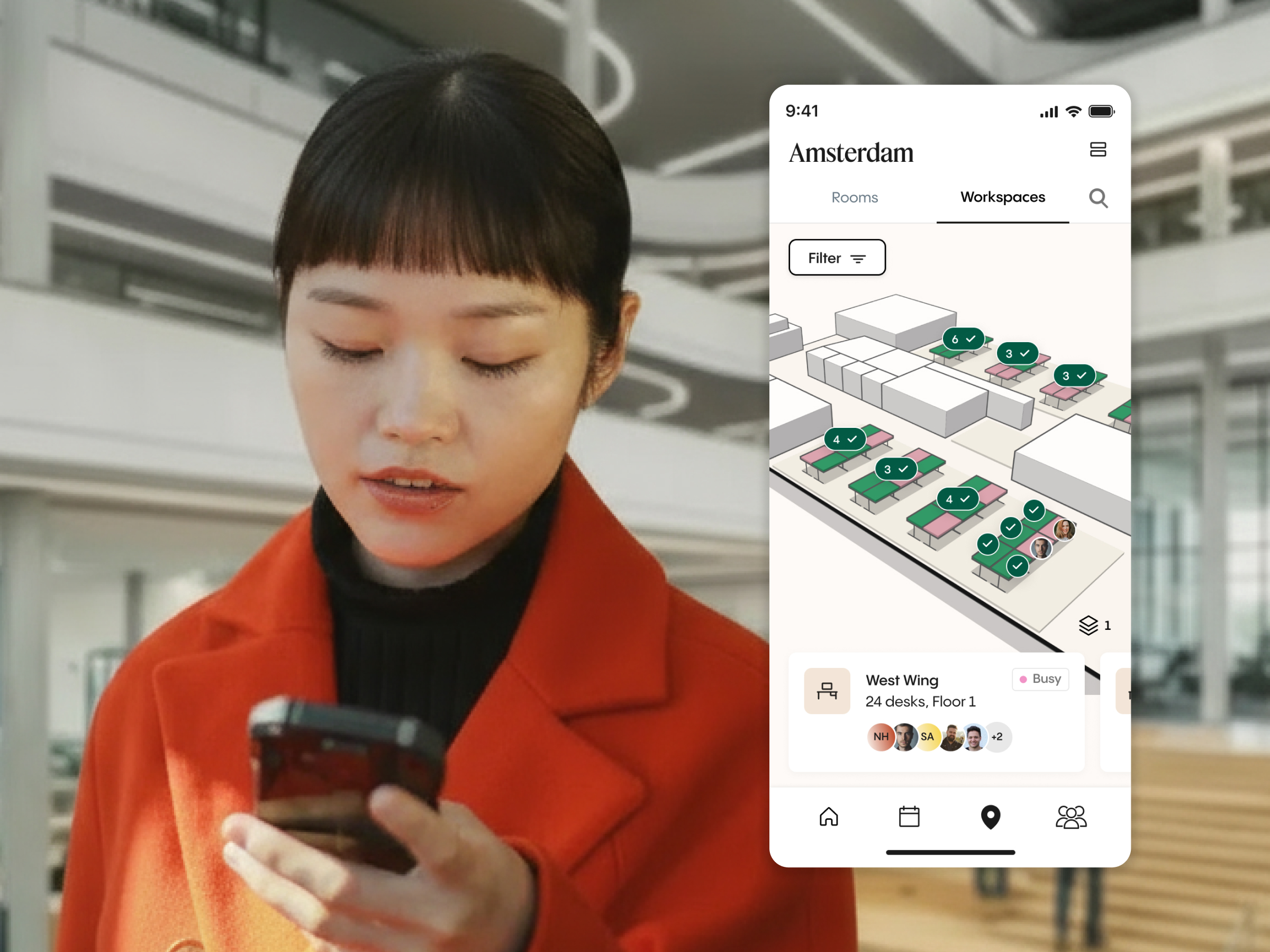

When the office does not support the work people plan to do on-site, short visits become more likely. If it is hard to find quiet space, meeting rooms are scarce, or desk setup takes too long, the cost of staying rises and the value of leaving increases.

Coffee badging is often a signal of a gap between the office’s intended role and its actual ability to support day-to-day work.

What coffee badging reveals about workplace expectations

Coffee badging is not only an attendance pattern. It is also a reflection of how the organization communicates expectations, evaluates contribution, and builds trust.

Presence vs productivity

When employees believe presence is being measured more than impact, they will allocate effort toward visible signals. Coffee badging can indicate that the organization’s “inputs” (time and presence) are easier to observe than “outputs” (results and quality), and are therefore being over-weighted.

This is especially common in functions where work is less tangible, cross-functional, or long-cycle. In those contexts, employees may use visibility as a substitute for clarity about what success looks like.

Autonomy vs control

Hybrid work often rests on a promise of autonomy: choose where to work based on the task. If attendance policies feel like control mechanisms rather than enablers of collaboration, coffee badging becomes a way to regain autonomy while still complying.

The behavior can also reflect inconsistent leadership. If different managers apply expectations differently, employees may prioritize the safest, least ambiguous option: appear briefly to reduce questions, then return to the environment where work feels most manageable.

Cultural signaling

Coffee badging can function as cultural participation. A short visit may be used to show membership in a team, be present for informal conversations, and demonstrate alignment with the organization’s norms.

At the same time, when cultural expectations are implicit, employees may over-index on symbolic acts. The result is a workplace where signals of commitment are visible, but the underlying experience of work is less connected to the office.

Trust dynamics

In many organizations, the debate about attendance is also a debate about trust. Coffee badging can be a response to low-trust dynamics where employees feel monitored, and leaders feel uncertain about accountability in hybrid work.

Coffee badging is often a signal of partial trust: enough confidence to allow flexibility in practice, but enough skepticism to keep “being seen” as a defensive behavior.

Common coffee badging patterns employers observe

Coffee badging shows up differently depending on the role, commute, office setup, and cultural norms. The scenarios below describe patterns employers commonly notice in hybrid attendance patterns.

- The meeting-only commuter. An employee arrives for a key in-person meeting, contributes actively, and then leaves soon after. The office visit is tied to a clear event rather than a full-day schedule.

- The morning visibility loop. Someone comes in early, greets colleagues and leaders, spends time in shared areas, and departs before peak desk usage. The visit creates social presence but does not translate into sustained occupancy.

- The “drop-in between commitments” pattern. An employee uses the office as a waypoint between external meetings, school pickups, or personal appointments. The office functions as a flexible resource, not a fixed location for the day.

- The team-day spike with fast taper. A department shows high arrival volume around a team moment, such as a stand-up or planning block, followed by a noticeable reduction in occupancy. Collaboration is concentrated, and individual work is relocated elsewhere.

- The amenity-centric visit. Employees cluster around café spaces, lounges, or social zones for a short period, then disperse. The office is used primarily for connection, not desk-based work.

- The “just-in-case” appearance. An employee visits briefly to avoid being perceived as absent, especially during leadership visits, project milestones, or periods of organizational change. The behavior reflects uncertainty about how attendance is interpreted.

These scenarios do not require a single motivation. The same person may coffee badge for different reasons across different weeks, which is why interpreting the pattern needs context rather than assumptions.

Why coffee badging matters for employers

For employers, coffee badging matters because it changes how the workplace functions and how reliable workplace signals become. When on-site presence is brief and uneven, workplaces often struggle to understand which desks and spaces are actually needed on a given day, especially without structured ways to booking shared workplace resources. The most important impacts are operational and cultural, not moral.

Office utilization data

Short visits can distort the meaning of utilization. Badge swipes and entry counts may look healthy, while sustained occupancy remains low. Conversely, a day can appear “busy” because of morning arrivals even if desk and room usage is modest after midday.

This matters when organizations use utilization to justify real estate decisions, service staffing, or workplace investments. Coffee badging behavior can produce data that is accurate in measurement but misleading in interpretation.

Coffee badging is often a signal of measurement mismatch: leaders track presence events, while the workplace needs insight into duration, purpose, and patterns.

Workplace planning

Workplace teams plan for demand: desk availability, meeting room capacity, reception load, food and beverage, and cleaning schedules. Short, concentrated visits increase volatility. Entrances and shared amenities may experience peaks, while neighborhoods remain underused.

This creates a planning challenge: services need to handle spikes, but the overall day may not justify full resourcing. Over time, that mismatch can lead to either over-provisioning (higher cost) or under-provisioning (worse experience on peak moments).

Employee experience

If the office is experienced as a place to “be seen” rather than a place to do meaningful work, the office value proposition weakens. Employees may start treating on-site time as overhead and optimize for minimizing it.

This can also create inequity between roles. People with long commutes, caregiving responsibilities, or concentrated focus work may feel penalized by expectations that reward visibility over outcomes.

Trust and engagement

Coffee badging can produce a subtle engagement cost. When employees feel they need to manage impressions, psychological safety can decline, and the relationship between employer and employee becomes more transactional.

For leaders, the risk is interpreting coffee badging as defiance rather than information. Misreading the behavior can lead to tighter controls that increase compliance theater, not collaboration.

Coffee badging is often a signal of unclear reciprocity: the organization asks for presence, but employees are not convinced the office consistently returns value.

Coffee badging compared to other attendance behaviors

Coffee badging is part of a broader landscape of return-to-office behavior. The distinction is not primarily about right or wrong, but about what each pattern suggests about work design.

- Compared to typical hybrid attendance: Hybrid attendance patterns often include full on-site days and full remote days. Coffee badging sits in between, emphasizing short, purpose-limited visits and creating more time-of-day variability.

- Compared to presenteeism: Presenteeism is associated with being physically present in ways that may not support performance or wellbeing. Coffee badging overlaps in the sense that visibility can be the driver, but it tends to compress presence into a smaller window rather than extending it.

- Compared to flexible on-site work: In genuinely flexible environments, on-site time is aligned to task needs and team coordination. Coffee badging can resemble flexibility, but it often appears where the rationale for being on-site is ambiguous, contested, or primarily symbolic.

These comparisons matter because they affect how leaders interpret patterns. The same observed behavior can have different implications depending on whether the office is treated as a collaboration hub, a compliance location, or a service people use when it helps.

When coffee badging is a signal, not a problem

Coffee badging is not automatically harmful. In some contexts, it can be neutral, expected, or even efficient.

- Role-based on-site needs vary. Some roles require presence for specific moments, such as stakeholder check-ins, workshops, or equipment access. Short visits can reflect legitimate job design.

- The office is optimized for collaboration, not deep work. If the office primarily supports meetings and social connection, it is rational for employees to leave for focused work once collaboration is complete.

- Commute and energy management are real constraints. In cities with long commutes, a full-day office expectation may be disproportionately costly. Short visits can be a sustainable compromise that maintains connection without exhausting employees.

- Teams have concentrated overlap windows. Distributed teams may only have a few hours of overlap across time zones or schedules. On-site time may be concentrated around those windows by design.

- The organization is in transition. During policy changes, reorganizations, or office redesigns, patterns can temporarily fragment. Coffee badging may reflect experimentation before a stable rhythm emerges.

In these situations, the signal is not “people are avoiding work.” The signal is that employees are actively optimizing around constraints, and leaders may need better alignment between expectations and workplace realities.

How employers can respond without overcorrecting

Employers typically want to increase meaningful time together, not simply increase badge events. The most effective response is strategic: clarify what on-site time is for, design spaces that support those purposes, and interpret data with care.

Clarifying expectations

Organizations benefit from explaining the purpose of on-site time in practical terms. That includes defining which activities are best done in person, which decisions should happen together, and what “good attendance” looks like beyond hours in a building.

Clarity reduces the need for impression management. It also makes performance conversations less dependent on proximity and more dependent on contribution.

Aligning office design to work types

If leaders want sustained on-site time, the environment needs to support it. That does not require a single ideal office, but it does require alignment between:

- The kinds of work teams do on-site (collaboration, focus, learning, social connection)

- The spaces available (rooms, quiet zones, project areas, informal meeting points)

- The friction of being on-site (setup time, finding space, noise, basic services)

When office design aligns to real work types, coffee badging behavior often becomes less attractive because staying longer becomes more useful.

Using data carefully

Workplace data can be a powerful lens if it is interpreted with the right questions. Entry counts, occupancy, and room usage do not automatically explain motivation. Leaders get more value when they combine quantitative signals with qualitative context from teams.

A useful framing is to treat coffee badging as a pattern to investigate, not a problem to punish. That approach supports better decisions about scheduling norms, space mix, and service levels, while reducing the risk of turning attendance into a trust conflict.

Key takeaways for workplace leaders

- Coffee badging is often a signal of misaligned incentives between visibility expectations and how employees achieve productive work.

- Short office visits can distort utilization data, making entry volume look healthy while sustained occupancy remains low.

- Coffee badging behavior can reflect uncertainty about how attendance is evaluated, especially in low-trust or inconsistent management environments.

- The most effective response is clarifying the purpose of on-site time and aligning office design to the work people are expected to do in person.

- Not all coffee badging indicates a workplace problem; in some contexts it is a rational outcome of commute constraints, role needs, and collaboration-focused office use.

- Treat coffee badging as an insight into hybrid system design, not as a moral judgment about employee intent.